Srishti Jha

UGIII

Roll no. : 001600401029

During the pre-Christian era[i] in the Scandinavian region of Northern Europe, the ethno-linguistic group that dominated this region were termed as the Germanic people by Roman-era authors. They were possibly speakers of early Germanic languages, which later had an influence on the English spoken today. Scandinavia consisted of areas known in the modern world as Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. However, in colloquial English usage, ‘Scandinavian Peninsula’ broadens the horizon to include Finland and Iceland. This group is known by another term, namely, Nordic countries.

Map of Scandinavia, Google Maps

Map of Scandinavian Peninsula, Google Maps

The Viking Age of Scandinavian history refers to the period between the last decade of the 8th century AD and mid-11th century AD. This is when the Norman conquest of England took place in 1066 by the joint Norman, Breton, Flemish and French armies, led by the Duke of Normandy, later known as William the Conqueror. The Vikings were historically known for their violent raids on their neighbouring areas, their conquests, and their efforts at preventing the Christianisation of Scandinavia, as they were pagans. Old Norse was the proto-Germanic language that somewhat united these people. Also known as Norsemen, there have been many stories surrounding their religion told and retold over centuries. We know these stories as Norse mythology.

Sea-faring Danes depicted invading England. Illuminated illustration from the 12th century Miscellany on the Life of St. Edmund.

- NORSE MYTHOLOGY: AN OVERVIEW

Norse mythology is the entire body of folklore, encompassing the myths stemming from Norse paganism, the religion followed by the Vikings. The sources, which have fed these myths and kept them alive till the modern day, were a compilation of runic inscriptions and Skaldic poetry[ii]. Possible Christian retellings of those myths have also rendered them more as folklore rather than actual accounts of a pre-existing polytheist religion in a Christianised Scandinavia.

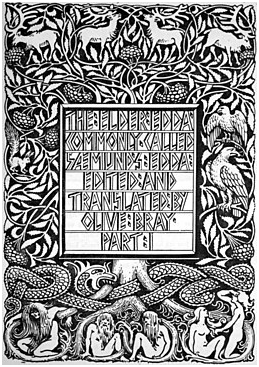

The textual sources of Norse mythology were written in the 12th and 13th centuries in modern-day Iceland. These sources are written in Old Norse, which was the language of Scandinavia in the medieval era. However, most of this poetry stems from much older oral traditions of poetry, so they can be dated much earlier than these sources. The two chief sources of Norse mythology are The Poetic Edda and The Prose Edda. The Poetic Edda, also known as the Elder Edda is a compilation of poems about Norse gods and heroes. Although this collection was written in a manuscript named the Codex Regius in 1270 AD, many of its poems can be dated as early as anywhere between 800-900 AD. The Codex Regius is not the original manuscript, but the duplicate of another manuscript written in 1200 AD. This is the sole written evidence of authentic pre-Christian traditions of Scandinavian mythology and religion, before its Christianisation from the 11th century onwards.

The title page of Olive Bray’s English translation of Codex Regius entitled Poetic Edda depicting the tree Yggdrasil and a number of its inhabitants (1908) by W. G. Collingwood.

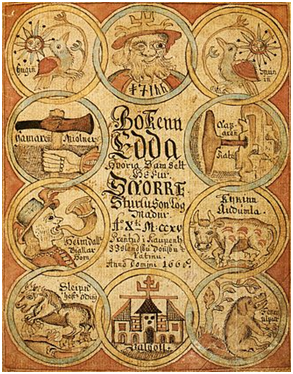

The Prose Edda, also known as the Younger Edda, is a work of prose by Icelandic author Snorri Sturluson, published in 1220 AD. Sturluson was unhappy with the rise in popularity of European models of poetry in his country, particularly the English and French style ballads. He wanted to make Skaldic poetry, a complicated form of Old Norse poetry, more popular and accessible among his countrymen. This is why he wrote The Prose Edda as a handbook for Skaldic poetry, which were composed of kennings, or complicated allusions to Norse myths. His book is more of a secondary source and is possibly written to make the myths relevant in a Christian world. Sturluson was a medieval Christian and his work is more of an example of euhemerization, rather than an actual source of Norse mythology.

Print edition of Snorri’s Edda of 1666

The Norse pantheon of gods consists chiefly of two families, namely the Aesir[iii] and the Vanir. These two families initially fought for supremacy, but later reconciled after discovering that they were equally powerful and could perhaps rule together. Odin, one of the most revered gods of Norse mythology, belonged to the family of Aesir, along with his wife Frigg and sons Baldr and Thor. This paper is going to trace the origins of Thor in Norse mythology and make a comparative study between the original story of the Norse God of Thunder and his character in cinematic adaptations. It will analyse how a myth persists over ages and in what ways is it modified to make it more relevant centuries after its formation.

- THOR, THE NORSE GOD OF THUNDER

While Odin was the most prominent God in the Norse myth, often known by the name ‘Allfather’ among others[iv], Thor is the most popular God among the worshippers. The son of Jord (meaning ‘earth’), a giantess and Odin, Thor is portrayed as a fighter in the poems and the stories of The Poetic Edda and The Prose Edda respectively. He is often described as an extremely tall and muscular man, with red hair and always bursting with the urge to fight all the time. The image is undoubtedly hypermasculine, one that seems to be modelled on the image of an average Viking warrior. His connection to such a commonly favoured image may well be the reason behind his popularity.

Thor’s Fight with the Giants (1872) by Mårten Eskil Winge.

According to the myths, Thor is the protector of both Asgard, the abode of the Norse gods, and Midgard, the realm where human beings live. He is more of a people’s god compared to Odin. While people on Earth live in perpetual fear of crossing the Allfather’s path, because he is notoriously known for causing fights and collecting the dead warriors in his hallowed palace, Valhalla, for Ragnarok[v], Thor is popular owing to his image as a protector. If there is one thing that truly completes Thor’s personality, then that has to be his fearsome hammer, Mjollnir.

In The Prose Edda, Thor gets his hammer as a gift from the dwarves Brokk and Eitri. The hammer is no usual tool, the things that make it a weapon and that too, a distinguishable one from other weapons, is its ability to strike anything it hits, come back to Thor from any place it lands at, and shrink to the size of an amulet, which Thor can wear around his wrist. The hammer is mentioned as Odin’s treasure in The Poetic Edda, but Snorri Sturluson writes about it in his book The Prose Edda, in the chapter titled ‘Extracts From the Poetical Diction (Skaldskaparmal). Loke’s Wager With the Dwarves’:

‘Then Brokk produced his treasures. He gave to Odin the ring, saying that every ninth night, eight other rings as heavy as it would drop from it; to Frey he gave the boar, stating that it would run through the air and overseas, by night or by day, faster than any horse; and never could it become so dark in the night, or in the worlds of darkness, but that it would be light where this boar was present, so bright shone his bristles. Then he gave to Thor the hammer, and said that he might strike with it as hard as he pleased; no matter what was before him, the hammer would take no scathe, and wherever he might throw it he would never lose it; it would never fly so far that it did not return to his hand; and if he desired, it would become so small that he might conceal it in his bosom; but it had one fault, which was, that the handle was rather short.”

Even in the constituents of Thor’s family, we see a connection to hypermasculinity. While his primary family includes his wife Sif and his children with her, he also sired children with other giant women he has slept with. His relationships with these women are framed as sexual victories fuelling the hypermasculine narrative. In both the Eddas, the tales concerning Thor are mostly about his prowess as a fighter. As the defender of two realms, he is mostly engaged in fights with the giants from Jotunheim, or with any other threatening entity. These tales deeply focus on his masculinity and become a parameter of judgement for his character. Snorri elaborates on it in the chapter ‘Thor’s Adventures’ in his book:

“Then said Ganglere: A good ship is Skidbladner, but much black art must have been resorted to ere it was so fashioned. Has Thor never come where he has found anything so strong and mighty that it has been superior to him either in strength or in the black art? Har answered: Few men, I know, are able to tell thereof, but still he has often been in difficult straits. But though there have been things so mighty and strong that Thor has not been able to gain the victory, they are such as ought not to be spoken of; for there are many proofs which all must accept that Thor is the mightiest.”

So the mighty Thor is perhaps not that mighty after all. He has had his share of defeats, but since his victories outnumber those defeats, the defeats are never spoken of. The Vikings are mostly known for their maritime expeditions, which were violent in nature according to Alcuin, a scholar from Charlemagne’s court:

“Lo, it is nearly 350 years that we and our fathers have inhabited this most lovely land, and never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race, nor was it thought that such an inroad from the sea could be made. Behold, the church of St. Cuthbert spattered with the blood of the priests of God, despoiled of all its ornaments; a place more venerable than all in Britain is given as a prey to pagan peoples.”

It would not have been possible for a god like Thor to be popular among the Norsemen, if he was shown as a warrior with even the slightest tendency to lose. This explains the nature of all the myths surrounding him. It is worth looking at the texts from the Elder Edda[vi] primarily featuring him, so as to establish this argument about Thor’s portrayal as a predominantly one-dimensional hypermasculine character in Norse mythology. The poems in The Poetic Edda featuring Thor and his adventures are namely ‘Harbadsljod’, ‘Hymiskvida’ and ‘Thrymskvida’.

- HARBADSLJOD

The title of this poem means ‘the song of Harbadr.’ Harbadr is another name of Odin, so many scholars have accepted the claim of Odin disguised as a ferryman and indulging in a match of insults with his son Thor. Those who know Odin from popular culture might find his character in Norse mythology appalling. In this particular poem, Odin isn’t a benevolent god, who wants nothing more than peace and has immense fatherly affection for his son. Instead, Odin is a scheming and maleficent being, who wants anything but peace. He instigates war among human beings and other creatures in order to collect warriors for Valhalla, who will later fight for him at the time of Ragnarok, the Norse doomsday. This is shown in this poem, where he keeps insulting Thor for being less manly than him and tries to prove so by talking about his sexual and fighting prowess.

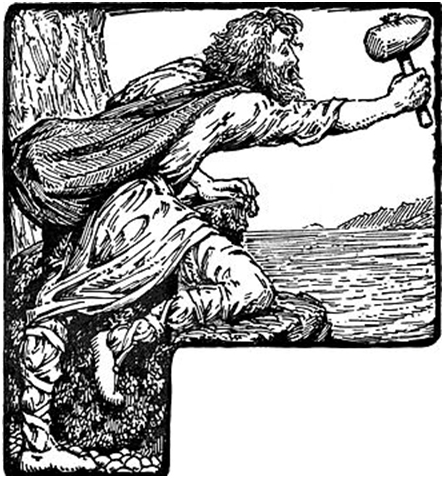

“Greybeard mocks Thor” (1908) by W. G. Collingwood. ‘Greybeard’ was another name of Odin, who was disguised as Harbadr here.

Thor, on the other hand, is shown as a simple man with only victories in fights with giants as his achievements. He is also shown somewhat dim-witted (this continues in other stories, where he is often shown as a man with more brawn than brains, someone who is easily tricked by figures like Loki), because he often fails to understand the insults that Harbadr throws at him.

“Thor threatens Greybeard” (1908) by W. G. Collingwood. In this painting, Thor gets back at Harbadr by insulting him.

However, an interesting thing that could be seen is the difference between Thor and Harbadr’s motivations to fight. This difference steers his character towards a more positive path and provides some sentiment to his hypermasculine arc. While Harbadr, who is actually Odin, fights with a selfish motivation, for the sake of personal gratification, Thor’s motivation to fight is more businesslike. He fights in order to restore peace in both Asgard and Midgard. That is his only reason to fight the Jotuns, and there is no complexity in this. This strengthens his personality and his undertaken duty as a protector. This is another reason why Thor was more popular as a god than Odin, and the poem makes this reason clearer. The following excerpt from the poem supports this statement:

Thor spake:

19. “Thjazi I felled, | the giant fierce,

And I hurled the eyes | of Alvaldi’s son

to the heavens hot above;

of my deeds the mightiest | marks are these,

That all men since can see.

What, Harbarth, didst thou the while?”

Harbarth spoke:

20. “Much love-craft I wrought | with them who ride by night,

When I stole them by stealth from their husbands;

A giant hard | was Hlebarth, methinks:

His wand he gave me as gift,

And I stole his wits away.”

Thor spake:

21. “Thou didst repay good gifts with evil mind.”

Harbarth spake:

22. “The oak must have | what it shaves from another;

In such things each for himself.

What, Thor, didst thou the while?”

Thor spake:

23. “Eastward I fared, | of the giants I felled

Their ill-working women | who went to the mountain;

And large were the giants’ throng | if all were alive;

No men would there be | in Mithgarth more.

What, Harbarth, didst thou the while?”

Harbarth spake:

24. “In Valland I was, | and wars I raised,

Princes I angered, | and peace brought never;

The noble who fall | in the fight hath Othin,

And Thor hath the race of the thralls.”

- HYMISKVIDA

This poem is a more simplistic portrayal of Thor’s strength and the will to strive against all odds, further adding to his image of an unyielding fighter. In order to get a cauldron that can fit enough ale for the gods, Thor goes with Tyr, a fellow Aesir god, to Tyr’s stepfather Hymir’s house. Hymir was a giant notorious for his temper. This poem describes a series of challenges that both Hymir and Thor have to fulfil in order to secure that masculinity, which include fishing (where Thor accidently catches Jormungundr, the Midgard serpent and the offspring of Loki and fights against it), a contest where Thor has to break Hymir’s favourite cup in order to get his cauldron and the slaughtering of the giants by Thor towards the end. This established his supreme position over the giants yet again.

The Jotuns in Norse myth are not like the typical giants shown in popular culture. Rather, they belong to the same species as the gods, even marrying and breeding with them. The giants and the gods are more like two rival families in Norse mythology, which makes their struggle for supremacy even more meaningful. In this context, Thor’s ability to kill giants is what makes him a desired masculine mythical figure. This poem is simply a saga of Thor’s strength as a protector and god.

Thor’s foot goes through the boat as he struggles to pull up Jormungundr in the Altuna Runestone.

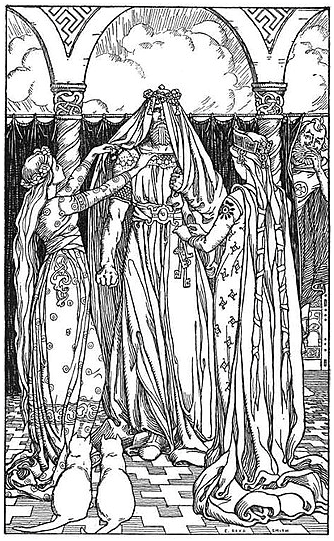

- THRYMSKVIDA

This poem is one of the finest poems from The Poetic Edda, and also one to portray the Norse god in an unusual way, probably intended for comic relief. In this poem, a giant named Thrym steals Thor’s hammer and agrees to return it only on one condition; provided he gets the hand of the beautiful Vanir goddess Frejya. Because of this demand and Frejya’s refusal to give in to this demand, Thor has to dress up as the bride on Heimdall’s suggestion. In this getup, he embarks on the journey to Thrym’s house, with Loki as his buddy (who was disguised as a maiden).

Apart from the obvious comical elements in the poem, what is seen here is Thor’s refusal to bend gender roles even in the slightest. He is shocked at the idea of wearing a woman’s dress, as can be seen in these lines:

14. Then Heimdall spake, | whitest of the gods,

Like the Wanes he knew | the future well:

“Bind we on Thor | the bridal veil,

Let him bear the mighty | Brisings’ necklace;

15. “Keys around him | let there rattle,

And down to his knees | hang woman’s dress;

With gems full broad | upon his breast,

And a pretty cap | to crown his head.”

16. Then Thor the mighty | his answer made:

“Me would the gods | unmanly call

If I let bind | the bridal veil.”

“Ah, what a lovely maid it is!” (1902) by Elmer Boyd Smith. Thor is getting ready to marry Thrym here.

Thor is incomplete without his hammer, and that implies here that with his hammer missing, he will be left defenseless against the citizens of Jotunheim. But even that fear doesn’t change his idea of masculinity. He is more scared of being stripped of his manliness than of jeopardizing the lives of those he is supposed to protect. However, Loki surprisingly reminds him of his duties in these following lines:

17. Then Loki spake, | the son of Laufey:

“Be silent, Thor, | and speak not thus;

Else will the giants | in Asgarth dwell

If thy hammer is brought not | home to thee.”

While Thor was a representative of traditional masculinity, his masculinity couldn’t be called normative because of a few instances in the mythology. Loki, Odin’s blood brother and the one known for his tricks and mischief, is actually the mother of Odin’s eight-legged stallion Sleipnir. According to the sources, Loki had transformed into a mare in order to distract a stallion named Svadilfari. Later, the mare mated with the stallion to give birth to Sleipnir. Loki, in contrast to Thor, seamlessly shifted through the traditional gender norms. He instantly changed into a maiden in order to accompany Thor and unlike him, did not have the need or urge to fiercely protect his masculinity. Therefore, this poem is another instance of Thor being co-dependent on his traditional hypermasculine image.

However, a comparative study of Thor the Norse God with his character in modern cinematic adaptations will bring forth the polarities of the two archetypes. The study will attempt to show Thor’s evolution from a strong god to someone with a multidimensional character arc, and more pertinently, someone we can relate to, in a time and age where personal beliefs and traits are gradually being considered over society’s expectations from all of us.

- THOR ODINSON, THE GOD WHO BECAME A SUPERHERO IN THE MARVEL CINEMATIC UNIVERSE

The Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) is an American media franchise and shared universe centered on a series of superhero films, independently produced by Marvel Studios and based on characters that appear in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. The franchise also comprises of television shows, merchandise and a host of other digital products. The universe is connected by various characters, plot elements, storylines and an underlying theme of justice and protection of this world from both human as well as intergalactic villains.

Marvel Cinematic Universe inter-title from Marvel Studios: Assembling a Universe (2014)

The most popular ensemble of superheroes that MCU has provided to this world is the Avengers, a group of individuals working together to keep the evil forces at bay, while battling their own issues, ranging from the physical and mental to the personal and circumstantial. What distinguishes this franchise from other franchises is the detailed interconnection of plots throughout the movies, all leading to one big picture, the final battle against some of their most formidable opponents, while showing them as beings, human or otherwise, with actual struggles and issues instead of a bunch of perfect superheroes never getting defeated, no matter what.

The Avengers consist of distinguished fictional individuals like Captain America (Steve Rogers, an American super soldier fighting against the Nazis in World War II), Iron Man (Tony Stark, a scientific visionary and billionaire owner of Stark Industries, a global technology conglomerate), Black Widow (Natalia Romanoff, a former KGB spy and skilled martial arts expert), Hulk (Dr. Bruce Banner, a brilliant scientist struggling to adjust with his alter ego), Captain Marvel (Carol Danvers, a former US Air Force pilot), and others, among which Thor, the prince and apparent heir of Asgard, is a member.

The theatrical release poster of The Avengers (2012), featuring Chris Hemsworth (on the right) as Thor

In the MCU, Asgard isn’t the cold and desolated Norse kingdom, but a city with futuristic architecture and an advanced civilization. Odin isn’t the mean being as his Norse equivalent, but a benevolent king, who fights only for the sake of peace in the nine realms. He has two sons, Thor, his elder son, and Loki, his younger son, who turns out to be adopted from Jotunheim, when Odin had gone there to fight Loki’s father Laufey. Thor appears majorly in seven MCU movies, out of which five movies will be discussed here, namely the Thor trilogy (2011-2017), Avengers: Infinity War (2018) and Avengers: Endgame (2019). The development of his character arc can be seen through an analysis of his role in these movies.

- THOR TRILOGY (2011-2017)

In the first movie of this trilogy named Thor (2011), Thor, played by Australian actor Chris Hemsworth, is shown as a young Prince of Asgard, who is the rightful heir to the throne as Odin’s successor. Loki is not his uncle here, but his younger brother, who resents him for not being treated equally. His mother isn’t Jord, but Odin’s wife Frigga ( based on Odin’s wife Frigg in the myths), perhaps owing to Odin’s image as a monogamous, loving family man, thus making his character more acceptable to an audience not that well equipped with the original myths and their nuances.

Thor is the same hypermasculine character in this movie, sans his duty to protect both Asgard and Midgard. He is an arrogant brat, finding every opportunity to channelise his overflowing energy and strength. When a group of giants from Jotunheim attack Asgard on the day of his coronation, Thor goes back with his warrior friends to Jotunheim in order to avenge this attack, despite his father’s repeated warnings. As a punishment for breaching his father’s orders, Thor is banished to earth by Odin and his hammer thrown towards the same place. The inscription on Mjollnir says “Whosoever holds this hammer, if he be worthy, shall possess the power of Thor.” Ultimately, Thor is able to wield Mjollnir again, after he learns the importance of putting others before himself and realizing the importance of humility. Compared to the myths, Sif is not his wife in the movies, but his friend. He falls in love with a young astrophysicist named Jane Foster in the movie. The movie unfortunately falls apart in the depiction of the complexities of a god falling in love with a mortal woman and doesn’t give enough space to Thor to fully explore his humanity while on earth.

Thor as a dim-witted fighter in Thor (2011)

The second film in this trilogy is Thor: The Dark World (2013). This movie is one of the weakest movies in the entire MCU in terms of plot, character and the overall flow. It adds nothing to Thor’s character and if anything, builds upon his one-tone approach in the previous film. In both Thor and Thor: The Dark World, the blond god is shown as a muscled man fighting to save the honor of his kingdom and the love of his life, with zero introspection into his motivations as a god and a fighter, or even as a lover. There is no wonder that both these films are disliked by critics and fans alike.

Thor: The Dark World (2013)

All this negativity is shoved aside to give way to what could possibly be the rebirth of Thor in Thor: Ragnarok (2017), the third installment of this trilogy. Imagine the way Thor has been portrayed in both the myths and the movies, and strip all the things that make him a fighter or define him and his masculinity in any way. What we’re left with then is a man with the destiny to be a great god and king, but full of self-doubts, insecurities and a multitude of issues to deal with. This man has to build everything from scratch, because whatever he knew about life and himself had little or no semblance with his reality. He has to reconstruct his identity, his masculinity and his strengths on the knowledge of his weaknesses and limitations. All of this has to be done along with his commitment to fight against evil, with a heightened sense of righteousness; to protect his people and the people of the earth, a sense which was missing earlier. This isn’t the Thor we have known, but this is the Thor in this movie, and there was no looking back from here.

Thor: Ragnarok (2017)

In this movie, it is revealed that Odin’s firstborn, Hela (possibly based on Hel, Loki’s daughter and the ruler of underworld in the myths) has come back to wreak havoc on Asgard and destroy the kingdom to avenge the wrongs done to her. In the first encounter with Thor, she completely destroys his hammer Mjollnir, which could possibly be termed as the first brutal attack on Thor’s hypermasculinity. Without his hammer, Thor was defenseless in the Norse myth, particularly seen in the poem ‘Thrymskvida’. His hammer was what defined him so far. One can only imagine what he must have gone though at that moment, something even his Norse counterpart didn’t have to go through. Stripping him of the one possession that defined him and his masculinity is a huge risk that movie’s director Taika Waititi took with the Norse god’s cinematic portrayal. Yet, this risk was necessary. It was necessary to subvert all ideas that both the readers of Norse mythology and Marvel Comics associated with the Thunder god; because this reinvention made him more human and connected him more to the crux of Norse mythology: Norse gods are not gods in the strictest sense, but personalities, serving more as role models than fear inducing divine beings. Throughout the movie, Thor fights evil creatures without his hammer, with the help of his brother Loki and Valkyrie, a woman belonging to the extinct clan of fierce women fighters hitherto responsible for safeguarding the throne of Asgard. Towards the end, Hela isn’t defeated by Thor, but by the demon Surtur, who ultimately destroys Asgard in Ragnarok. However, Thor isn’t ashamed of admitting his limitations and willfully accepts the incoming Ragnarok, saying that ‘Asgard is not a place, but a people.’

Thor’s reinvented character arc is further enhanced by his role in the MCU’s most recent culmination, namely Avengers: Infinity War (2018) and Avengers: Endgame (2019).

- AVENGERS: INFINITY WAR (2018) AND AVENGERS: ENDGAME (2019)

Avengers: Infinity War (2018) was the first part of the final tribute to a decade of MCU, a fitting end to this cinematic marvel (no pun intended), a spectacle in itself and a movie which took major risks at the expense of the usual expectations from a typical blockbuster movie; a reliable plot with not-so-shocking storyline. Infinity War does the exact opposite. The villain of this movie, a purple genocide-supporting megalomaniac named Thanos, actually fulfills his aim of wiping out half the population of the universe in order to fulfill his twisted aim of restoring balance in the universe. In a movie like this, it is impossible to imagine Thor doing anything but usual.

In fact, Thor plays a major role in the progression of the plot of this film. In the beginning, the events take place from the end of Ragnarok, when Thor, along with Loki, Valkyrie, Heimdall and the surviving Asgardians escape in a rescued ship to earth. However, they are caught by Thanos in space. While Valkyrie reportedly escaped with some of the Asgardians, Heimdall and Loki were not so lucky. In an emotional scene depicting Loki’s death, Thor cries to his heart’s content and mourns the death of a brother, with whom he always had a bittersweet relationship. After losing his entire family and home, Thor sets out to avenge them by killing Thanos with the help of the Guardians of the Galaxy, a group of intergalactic beings doing the job of protecting space and other planets from evil people. However, it is to be noted that Thor is still without his hammer. Along with two Guardians, Rocket Raccoon and Groot, Thor sets out to journey towards Nidavelleir, the home of the dwarves, master craftspeople capable of forging weapons and other advanced technology. However, on reaching there, Thor is greeted with hostility by Eitri (based on the dwarf Eitri, who made Mjollnir along with his brother Brokk in Norse mythology) and gets to know that all the dwarves have been slaughtered by Thanos. In order to get a new weapon, Thor had to take the risk of absorbing the power of the neutron star, which could get him killed. However, this time, Thor does something that could be termed traditionally masculine, but with a more selfless motivation. This is what makes him different in this case. After getting his new axe, Stormbreaker, Thor marches towards earth to fight with Thanos. In fact, at the end, it is Thor who managed to strike Thanos. However, because of a tiny miscalculation, he fails to stop him and is struck by disbelief and guilt at the end.

Thor gearing up to fight Thanos with his axe, Stormbreaker in Avengers: Infinity War (2018)

In Avengers: Endgame (2019), we see a guilt-ridden Thor getting ready to kill Thanos in a second attempt. He manages to do so, but realizes that he cannot undo the damage caused by the purplehead. Fast forward to five years, and we see a bulky Thor, playing games and fighting with kids over phone in a perpetual state of drunkenness. He lives in a shack in new Asgard, a place under construction by Asgardians, under the leadership of Valkyrie, in Norway. Hulk and Rocket Raccoon, who go to New Asgard to fetch him, are shocked to see Thor like this. This twist in Thor’s character is possibly the biggest twist and the most dangerous risk the movie directors Russo brothers could’ve ever taken. To show a fit, muscular man at the peak of his youth gradually descend into a state of sloppiness is something that can either make or break his character. According to some, this development broke his character and made a joke out of him. While others argue that this development made his character arc the strongest arc in MCU and an unprecedented move to make cinema, particularly mainstream cinema more inclusive and less stereotypical.

Thor in Avengers: Endgame (2019).

Anyone saying that ‘fat Thor’ is a joke is missing the point. In a culture that routinely shames people for mental health issues and body shaming people not conforming to the set beauty standards, Thor’s development brings forth the reality of people going through illnesses like depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and low self-esteem owing to repeated body-shaming. All these issues are real, and they go beyond our culture’s shameless negative stereotyping of people suffering from mental illnesses as ‘attention seekers’ and fat people as ‘lazy people’.

Cinema has historically added fuel to these stereotypes and does nothing to counter them as an influential genre. It is only now that more and more people are talking about it and more people are being open about their experiences. If a historically strong, masculine Norse god and comic character suffers from the same issues that people usually suffer from, then there is hope for a more nuanced understanding of mental health and body image issues. The best part about the movie is the way Thor’s weight issues were handled. When he finally goes out to fight Thanos, he does so without losing weight. Towards the end, when he crowns Valkyrie as the new queen and goes on a journey to truly discover himself, he does so without losing weight. The only things he deals with are his issues in a way as real as possible, though a little more screen time could have been devoted to this. Thor, the Norse God, the lord of thunder and lightning, ultimately experiences everything that a human being experiences. He realizes the importance of being who he actually is over being who he is supposed to be.

In this paper, the term ‘god’ doesn’t define a Norse god, hence there is an intentional refrain from using the term ‘God of so-and-so’ as much as possible. Norse gods weren’t defined solely by their roles as divine beings. They were more like personalities instead of godlike figures. This is what distinguishes their myth from other myths. Myths are the foundation of our culture, the crux of our existence. With time, their nature changes to make them more inclusive of new ideas, emotions and knowledge. Norse mythology, therefore, is more inclusive of these changes and over time, has undergone various changes and adaptations to suit the needs of the time. Thor’s character arc makes not only makes his myth relevant, but an integral part of the existing modern mythical canon.

[i] Iceland was the first Scandinavian country to be Christianised, followed by Denmark and Norway. By the late 12th century, all the Scandinavian countries were more or less Christianised.

[ii] Skaldic poetry is one of the two groups of Old Norse poetry, the other being the Eddic poetry. The term ‘Skaldic’ comes from the word ‘skald’, which referred to the court poets of the kings and leaders during the Viking Age. Skaldic poetry is complicated due to the usage of kennings, which are complicated allusions or mythical metaphors. If a myth is referenced in a Skaldic poem, then the authenticity of the myth is more reliable.

[iii] For the sake of clarity, I’ll use the anglicised spellings of the Old Norse words in this paper.

[iv] Odin speaks about all the names he is called by in this poem ‘Grimnismal’ from The Poetic Edda

[v] In Norse mythology, Ragnarok is a series of events, including a great battle, foretold to lead to the death of a number of great figures (including the Gods Odin, Thor, Týr, Freyr, Heimdall and Loki), natural disasters and the submersion of the world in water. After these events, the world will resurface anew and fertile, the surviving and returning gods will meet and the world will be repopulated by two human survivors, Lif and Lifthrasir. Ragnarok is an important event in Norse mythology and has been the subject of scholarly discourse and theory in the history of Germanic studies.

[vi] Since Snorri’s Edda is more of a retelling than an authentic source, therefore I’ll be analysing Thor’s character only on the basis of evidence found in The Poetic Edda, which is a much older and reliable written source of Norse mythology.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Avengers: Endgame. Dir. Joe Russo, Anthony Russo. 2019.

Avengers: Infinity War. Dir. Joe Russo, Anthony Russo. 2018.

Sturluson, Snorri. The Prose Edda. 1220.

Thor: Ragnarok. Dir. Taika Waititi. 2017.

Thor. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. Perf. Natalie Portman, Tom Hiddleston, Chris Hemsworth. 2011.

Thor: The Dark World. Dir. Alan Taylor. 2013.

Thorpe, Benjamin. The Poetic Edda. Norroena Society, 1907.