RUDRANI BOSE, UG III, ROLL NO. 23

Abstract : Myths are not static. The understanding and significance of myths change with time and differing social, political, historical and cultural contexts. Myths are reflective of human ideas and as ideas progress, or regress, the way a myth is viewed undergoes alterations. The myth of Leda and the Swan is a myth that has historically lent itself to becoming metaphors for things as diverse as the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and England’s treatment of Ireland. Yet the danger of using myth only as metaphor is that we might overlook the narrative of the original characters of the myth. This paper attempts to study the depictions of the myth of Leda and the Swan in the history of art, while exploring the portrayal of Leda as a woman with experiences of her own in these artworks , along with focussing on current feminist interpretations of the myth and the representation of women in myth.

A paper exploring mythography through art might include some attempt to define the terms “myth” and “mythography”. Yet the difficulty of this exercise quickly becomes apparent. G. S. Kirk writes in ‘ Myth: Its Meaning and Functions in Ancient and Other Cultures’ that “there is no one definition of myth, no Platonic form of a myth against which all instances can be measured. Myths . . . differ enormously in their morphology and their social function. . . .What I have tried to point out is . . . the persistent and distorting application of a false preconception, namely that “myth” is a closed category with the same characteristics in different cultures. . . General theories of myth and ritual are no simple matter.”1 There can be no one interpretation or understanding of a myth. How and why the same story is taken to mean different things ,by different people, contributes to the study of myths as a literary tradition open to change and interpretation. Yet myths are not confined merely to the written tradition, although that is what the etymology of the term “mythography” refers to. Merriam-Webster defines “mythography” as originating from two words myth and “graphein”. Myth is derived from the Greek “mŷthos”, meaning “utterance, speech, discourse, tale, narrative, fiction, legend,” of obscure origin. The Greek “graphien” refers to “writing or representation in a (specified) manner or by a (specified) means or of a (specified) object:”2 The word “representation” is particularly significant in this context. “Mythography”originally named the work of writers who generated written forms of myths from accounts in poetry , literature and public life. Myths have long been a part of oral cultures along with being a major influence on the visual arts such as painting, sculpture and film. Given the emphasis on “reading” myths, the exercise of “reading” meaning into works of art becomes important in order to explore the trajectory of the visual representation of myths.

The representation of myth in visual art has a long history and the way a particular myth is portrayed in a particular period of time is reflective of the social, historical, political and cultural context it belongs to. Yet the exercise of trying to attach some “meaning” to the myth is difficult. Ken Dowden and Niall Livingstone in ‘Thinking through Myth, Thinking Myth Through’ write that “It is exceptionally hard to describe the relation between a myth and its ‘meaning’ as it is applied to some new circumstance. There is something indirect about it, the recognition that the apparent meaning of the story (once upon a time …) must be transmuted into a rich new source of reflection and realization in a second level of meaning. This, according to Roland Barthes, was how myth worked. To study myth is, in this sense, to study meaning itself, to study systems of signification, namely semiotics.” 3

This paper deals with a particular myth, that of Leda and the Swan and explores how it has been variously represented in art across different periods of time, studying the transformations that myths undergo, since they are fixed and unchangeable. The very idea of a myth as “living” defines how different ages and different people choose to understand a myth in different ways. Art is particularly important in this context since it is a reflection of the representation of a myth in popular culture, drawn from prevailing intellectual traditions as well as popular understanding and influencing the latter as well. Given that the poem explores a specific political and gendered context, it is important to understand how we today “read” images of the myth in visual art. Dowden and Livingstone comment that “Myths are not, however, remembered in isolation: they are interactive, with each other and on countless occasions with every aspect of Greek life and thought. They are a continual point of reference, or system of references, and they constitute what since the late 1980s has been recognized in literature under the term ‘intertext’. ”4

This paper deals with a particular myth, that of Leda and the Swan and explores how it has been variously represented in art across different periods of time, studying the transformations that myths undergo, since they are fixed and unchangeable. The very idea of a myth as “living” defines how different ages and different people choose to understand a myth in different ways. Art is particularly important in this context since it is a reflection of the representation of a myth in popular culture, drawn from prevailing intellectual traditions as well as popular understanding and influencing the latter as well. Given that the poem explores a specific political and gendered context, it is important to understand how we today “read” images of the myth in visual art. Dowden and Livingstone comment that “Myths are not, however, remembered in isolation: they are interactive, with each other and on countless occasions with every aspect of Greek life and thought. They are a continual point of reference, or system of references, and they constitute what since the late 1980s has been recognized in literature under the term ‘intertext’. ”4

As Jenifer Neils says in ‘Myth and Greek Art: Creating a Visual Language’ , “there are two specific concerns of Greek painters and sculptors when faced with the challenge of narrating in visual, as opposed to literary, terms a specific story involving gods, heroes, or fantastic creatures. First, what devices did the artist employ for depicting a myth and how did this visual language come about? Second, how did the artist make his chosen theme relevant to a particular audience at a specific point in time? In order for a work of art to succeed in narrating a myth, it must employ a grammar understood by its viewers and relate in some fashion to the Zeitgeist of contemporary society”7

The myth of Leda and the Swan is complicated by the question of whether or not to view the act as one of sexual assault. Most paintings, especially those of the 16th century choose to portray it as a seduction. The amorous natures of the Greek gods and their unions with mortals are well documented in Greek myth. But the ambiguity of consent remains in all these cases and even if this were to be classified as a seduction, the fact that Jupiter is a god effectively ensures that Leda has little or no choice in the matter anyway. Then what are we to make of Leda, who is a woman and whose depiction is affected by how women are visualised at particular periods of time . The importance of Leda ends with the birth of her more famous children. She is a woman whose very identity seems to exist because of a rape or seduction and the chaotic consequences of the same. It is neither possible nor desirable today to relegate her into the shadows of her better known offspring, but rather, to recognise her as one possessed with her own story, her own experiences. Ironically, mythic characters cannot narrate their own experiences and must depend on the powers of others, literary or artistic to do so. Hence it becomes important to explore the various retellings of this myth by these other powers.

Vanda Zajko writes in ‘Women and Greek Myth’, “The question of how to characterise the relation of women and myth is primarily one of definition. For just as myth is widely acknowledged to be a problematic category that signifies quite differently at various historical moments, so too the designation of woman has no clear definition outside of specific cultural formations. There is an aspect of the combination of women and myth that complicates the issue still further: are we concerned here with myths in which women are regarded as the main protagonists or myths that have been creatively interpreted by or for women. Although both have continuously provided a resource with which writers and artists have explored the relations between the sexes, either within the landscape of myth itself, or in relation to the particular social and historical contexts of its various instantiations, the latter category has become particularly associated with the feminist interpretation of myth and thus with its explicit positioning as either liberating or oppressive for women”8

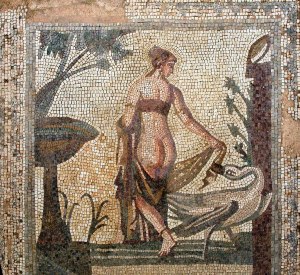

TIMOTHEOS

Leda and the Swan, Timotheos

One of the earliest representations of the myth of Leda and the Swan is this statue which is now a part of the Getty Museum. The Getty museum states that “found in 1775 in Rome, this statue is a first-century Roman copy of an earlier Greek statue from the 4th century B.C. attributed to Timotheos. More than two dozen copies of this statue survive, attesting to the theme’s popularity among the Romans. The contrast of the clinging, transparent drapery on Leda’s torso, especially over her left breast, and the heavy folds of cloth bunched between her legs characterizes Timotheos’s style. The statue both conceals and reveals the female body: a tension often found in sculpture of the 300s B.C., before actual female nudity became acceptable.”9 The swan appears in an intimate position with respect to Leda. Interestingly, Leda holds out a part of her garment in a manner that suggests a desire for concealment of the action. While the swan gazes into her face, Leda’s face is turned upwards to her left, a gesture that suggests a resignation ,to the impending union that is beyond her power to control.

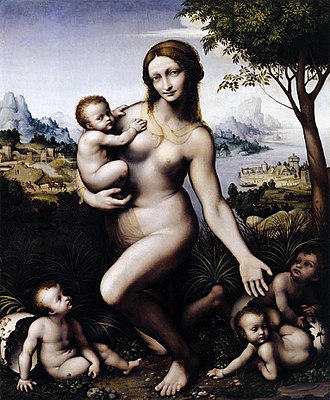

LEONARDO DA VINCI

Unfortunately, for a lot of paintings depicting the myth of Leda and the swan, the originals do not survive, what we have instead are copies based on assumptions of what the lost painting might have looked like. In 1504, Leonardo da Vinci started preparations for a painting that was to depicted a seated Leda with the swan, which he never completed. Instead, in 1508, he painted a standing nude Leda with the swan. This painting, by Cesare de Sesta is considered the closest copy of that now lost original.

In the painting, Leda appears to embrace the swan with pleasure, on her face is a look of peaceful serene delight. One wing of the swan fully embraces Leda’s body, almost as if it possesses her, claiming, as it may seem, some right of ownership of the female body before it. The swan also seems to be reaching out for further intimacy, expressing happiness or triumph while Leda almost coyly turns away her head a little, to look lovingly at her children. What is perhaps most significant is that this painting transcends barriers of time to show both the past and the present or perhaps the present and the future of the love making and the offspring that were a consequence of it, for the children who are to be the result of this union play near Leda’s feet. Is this a depiction of what is to happen, going beyond the scope of most paintings that depict only the sexual act or is it an alternate telling of the myth itself, where the relations between Leda and Zeus do not end after this one solitary union but continue into time. The backdrop of the painting, of the water at the bottom where the children play, the greenery and the hills evoke a peaceful beauty and further add to the happiness that is palpable in the painting. In the far off distance, one can spot a tall imposing building, perhaps a palace. This could be the palace of her mortal royal husband that Leda has left behind ,to be with the swan

Other close copies of this painting, differ subtly in their handling of the myth

The first painting is a copy by Giovanni Antonio Bazzi, also known as Il Sodoma and now lies in the Galleria Borghese. It is very similar to Sesta’s copy. Yet, the painting depicts only two of Leda’s four children, while right behind the child on the left lies a white egg. One could then pose the question of what changes that egg is to bring and whether it would then further damage this present idyllic landscape, which anyway must soon be damaged by the bloodshed and war caused by the offspring of this apparently amorous union,suggesting that although the scene immediately before us is one of picturesque tranquillity, it contains within itself the seeds of destruction.

The second is a sketch by Leonardo Da Vinci that is now a part of the Devonshire Collection. Unlike the previous painting, no children are present in this sketch and Leda’s body language seems ambiguous, seeming at once repelled by the swan and trying to escape from it, perhaps by an attempt to stand up as the posture of the legs would suggest, while being attracted to it,her hand almost pulling it closer. Like the other painting, the swan seems to be whispering into Leda’s ear, creating an atmosphere of intrigue by making the viewer wonder exactly what is being spoken between the two. The last painting is a copy of Da Vinci’s Kneeling Leda With Her Children by Giampietrino. Interestingly, this painting shows all four children yet does not show the swan. It depicts what happens after the sexual act without actually dealing with the act itself, explicitly implying that a foreknowledge of the myth is requisite on the part of its audience.

MICHELANGELO

This painting, is a restored version considered to be a very accurate depiction of the now lost painting of Leda and the swan by Michelangelo. The Royal Academy of the United Kingdom says that “The history of Michelangelo’s Leda, its cartoon and its copies, is complex. It is one of the oldest and largest drawings in the Royal Academy Collection but its real fascination lies in the fact that it replicates a long-lost work by Michelangelo. It was once thought to be Michelangelo’s original ‘cartoon’ (a full-scale preparatory drawing) for the painting of Leda and the Swan he produced for Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, in 1529-30. However, this attribution has since been challenged and the RA drawing is now thought to be a copy made by another 16th-century artist. or reasons which remain obscure, the artist never delivered the painting to the Duke of Ferrara but instead sent it and its cartoon to France with his assistant, Antonio Mini. There is little solid evidence for the whereabouts of these works once they reached France but the Renaissance art historian Giorgio Vasari was probably correct in his claim that Michelangelo’s Leda was acquired by King François I of France for his palace at Fontainebleau”10

Leda is seen reclining, the pleasure evident in her relaxed body language as tilts her head forward, almost appearing to be participating in a secret whispered conversation with Zeus disguised as the swan. Indeed the swan too looks up at her almost lovingly, while the embrace, through Leda’s extended leg, the arm that pulls the swan closer to her and the wing of the swan seems to envelop both of them in a protected cocoon of love and desire. Interestingly, the upholstery against which Leda reclines so peacefully is red in colour, seeming to be symbolic of carnal desire, creating a visual image of both peace and passion, love and tumult.

This is, then, the depiction of the myth as seduction, one of mutual consent. There is no fear, no expression of shock and surprise that an unanticipated attack would have caused. Such a portrayal caused outrage. The Royal Academy also writes in its website that “Michelangelo’s version of Leda and the Swan proved controversial and this possibly accounts for the disappearance of his original painting and cartoon. The painting is reputed to have been destroyed during the seventeenth century on the orders of Queen Anne of Austria because she objected to its ‘lasciviousness’. An inventory of the French royal collection made in 1691 records this iconoclastic act as well as the existence of a drawing ‘by Michelangelo representing a Leda’ which was earmarked ‘to be burned’. That drawing’s absence from subsequent inventories suggests that it must have indeed been destroyed, sold or given away”. 11

CORREGGIO

Correggio’s depiction of the Leda myth encompasses eight human figures and three swans, which significantly complicates comprehension of the painting. The pair in the centre of the painting seems easiest to decode as being Leda and Jupiter in a moment of intimacy not unlike what is depicted in the paintings previously discussed. Here too the swan’s body is spread out over Leda’s left leg, leaning forward towards Leda while she looks down at it serenely and almost indulgently. But then, who are the figures at the sides of the canvas. Some interpretations suggest that the painting might be depicting different timeframes, with the flying swan symbolising Jupiter flying away after the lovemaking, perhaps leaving Leda and their children to the destruction of war that must follow. Yet there is a third swan too, greeting another person. If that girl too is a Leda who has just encountered the swan and the other women are her female companions, then the question might arise as to why this Leda appears to shy away from the swan, for she is almost pushing it away. This complicates the depiction of what could have been, otherwise, a simple scene of seduction. According to this interpretation, Leda wishes, at first, to escape from the swan’s amorous behaviour yet later, for reasons unknown to us, assumes that expression of tranquility. This apparent tranquility might then be interpreted as what Yeats would later write. Correggio thus appears to amalgamate different opinions on Leda’s response into one painting. The swan flying away after the act of seduction adds to dramatic tone of the painting when placed directly overhead the first meeting, could the third nude figure then be Leda looking up at the swan as it flies away, juxtaposing different periods of time, that could be present and past, present and future or past and future depending upon which of the events represented in the centre and the top and lower halves of the right side one takes to be the present.

Yet, the left side of the painting too must be taken into account. A winged celestial figure leans back into the rock, looking down at two child like figures. The winged figure has been seen by some critics to be Cupid himself, while the children, might belong to Leda . The fact that there are only two children might be a reference to the version of the myth that claims -. The presence of Cupid, although initially evoking associations of amour, is also significant because it brings forth the ideas of violence that portrayals of Cupid evoked. These associations of violence are pre-eminent particularly during the Renaissance, of Cupid with a bow and an arrow. Even in Greek myth, where Leda and the Swan originally belong, Cupid plays a less than positive role in the myth of Apollo and Daphne. The imagery of military violence and war that is associated with Cupid is pertinent in terms of the violence that is inherent in what could be interpreted as a rape, as well as in the Trojan war and deaths that occur because of the children brought into being by this possible rape.

After looking at pictorial depictions of this myth, most of which are from the same time period, one might ask what ideas of ideology, society and history one can draw from these. If the myths are being examined as part of a study of the history of Western thought, or as a construction of symbols in whose repetition psychological truths emerge, what will be highlighted is not what the stories may have meant to the Greeks but the use that has been made of them by succeeding generations or the extent to which they might contribute to an understanding of mental life. In the three paintings that belong to the Renaissance, in the representation of a pagan myth of a god seducing or raping a mortal woman, perhaps the very paganism associated with the myth ensured that it was not to be seen as any reflection of the “mental life” of the real women of the renaissance, who as Joan Kelly points out that were relegated to the confining sphere of having to aspire for a higher spiritual love12. Yet there are similarities for even in the mythical world , one must wonder how much choice Leda actually had in the matter since it would involve refusing pleasure to a god. This absence of sexual freedom corresponds well with the situation of women, who not have a renaissance.

Zajko writes,“an excavation of the ‘mythic imagination’ has been seen as providing a way of exposing the deep roots of the misogyny that continues to contribute to the inequity of the world; once exposed, there is the opportunity for regrowth and change.”13. As pointed out previously, the whole myth is based upon the misogyny of men denying the power of consent to women, an act made possible by the sheer excess of power patriarchy affords to men over women. Jupiter’s status as a god may make him all powerful over Leda but this is a truth that also occurs in non-mythic worlds, through mortal men who assume god-like power over women. Myths have immense authority over popular culture and imagination, which only heightens the problems a myth like Leda and the swan might pose. Lillian Doherty writes that “ Myth is important to feminism because it is one element of literate culture that has the potential to incorporate womens traditions and perspectives… because myths are stories that combine an imaginative fluidity with an authoritative force, and because they are told in a variety of contexts even when they are also written down, they provide a point of entry for women’s perspectives and concerns in the discourse shared by women and men.”14

Myth and literature is populated by an extraordinarily large number of women, a fact,that in most ages ,unfortunately does not lead to any potency or power of women in influencing actual historical change. In ‘A Room of One’s Own’, Virginia Woolf observes of literary and mythical women that “Imaginatively, she is of the highest importance; practically she is completely insignificant. She pervades poetry from cover to cover; she is all but absent from history. She dominates the lives of kings and conquerors in fiction; in fact she was the slave of any boy whose parents forced a ring upon her finger. Some of the most inspired words, some of the most profound thoughts in literature fall from her lips; in real life she could hardly spell, and was the property of her husband… Mythical stories are fabulations of women, probably not created by women. In those narratives, as in other dominant discourses, they are used as metaphors. Still, contrary to official history, women have been important motors of mythical (his)stories. History comes from discord, and discord comes from women. Helen, Medea, Europa, Arianna, Io, and Phaedra were objects of rape, kidnapping, abandonment and betrayal; but they were also subjects of pleasure, of movement, of revenge”15

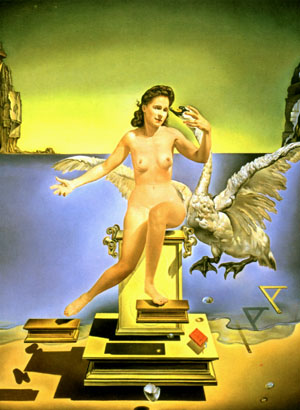

SALVADOR DALI

The Modernist period is marked by a number of references to the myth of Leda and the swan. These representations narrate the trajectory that a myth may take, without the resolution of certain fundamental problems in the way it has always been read. The Modernist Leda is different from the Leda of the Renaissance not because she is recognised as being the victim of misogyny but simply through being reduced to a metaphor for outrage. Such a reading too does not accord any importance to her own experiences but dehumanises her into a convenient literary tool. This involves Salvador Dali’s painting Leda Atomica which uses the myth to talk of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Dali’s painting depicts objects and the figures of both the swan and Leda in levitation. The swan seems to whisper in Leda’s ear, perhaps of the destruction that is to follow, paralleling the destruction of the world through nuclear bombs. No element comes in contact with each other and an egg shell harks back to the violent consequences of the union. This reduction of a woman, albeit mythical, into a political metaphor is very similar to Yeats’ representation of Leda,from where the title of this paper is also taken.16

There are several other depictions of the myth of Leda and the Swan in visual art that were too numerous to be discussed in detail here.

To conclude, art offers a space for the reinvention of older understandings of itself. Mythography can be seen as a process of re-vision and re-presentation. Myths do not mean for us what they meant to the ancient Greeks yet they are clearly important enough to be the enduring subject of visual art and literature. They reflect a way of thinking about the world and human beings have always changed their understandings of myths in order to reflect how they choose to view the world. As written before, the history of myths that deal with marginalised sections of society are particularly important since they narrate the history of discrimination faced by that particular group. An important example of what has been termed by some as ‘revisionist myth-making’ comes from Adrienne Rich’s essay ‘When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision.’ Here, Rich argues that the myths of the past continue to structure the experience and identity of women in the present and that their power must urgently be broken: “Re-vision – the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entertaining an old text from a new critical direction – is for women more than a chapter of cultural history: it is an act of survival. Until we can understand the assumptions in which we are drenched we cannot know ourselves. And this drive to self-knowledge for women, is more than a search of identity: it is part of our refusal of the self-destructiveness of male-dominated society. A radical critique of literature, feminist in it impulse, would take the work first of all as a clue to how we live, how we have been living, how we have been led to imagine ourselves, how our language has trapped as well as liberated us, how the very act of naming has been till now a male prerogative, and how we can begin to see and name – and therefore live – afresh”17. Zajko further elaborates, “Rich emphasises the continuity between representations of women in the past and those of the contemporary moment because of the shared assumptions that underlie them. The process of excavating these assumptions is the process of revision, which can thus be said to describe many mythographic enterprises”18. Mediums of art have always reflected the way society itself functions, be it the oral tradition of the myth in the classical world, the sculpture and the paintings or the written text of the poem. It falls to us to view all of these together as a part of an overarching enterprise of representation of cultural ideas. These enterprises must be excavated, and these assumptions must be studied in order to unravel and critique them.

ENDNOTES

- G.S.Kirk, ‘ Myth: Its Meaning and Functions in Ancient and Other Cultures’,quoted in William.G.Doty, Mythography: The Study of Myths and Rituals,(London: The University of Alabama Press,2000)

- Merriam Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mythography

- Ken Dowden and Niall Livingstone, “Thinking Through Myth, Thinking Myth Through” ,in ‘A Companion to Greek Mythology’(Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell Ltd,2001)

- Ibid

- Encyclopaedia Brittanica, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mythography

- Op Cit. Dowden and Livingstone

- Jenifer Neils, “Myth and Greek Art:Creating a Visual Language” in Woodard Robert ed. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology,( New York:Cambridge University Press,2007) .

- Vanda Zajko, “Women and Greek Myth” in Woodard Robert ed. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology( New York:Cambridge University Press,2007).

- Getty timotheos

- Royal Academy, United Kingdom,https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/leda-and-the-swan

- Ibid

- Joan Kelly-Gadol, ‘Did Women Have a Renaissance’, https://www.lettere.uniroma1.it/sites/default/files/622/Did%20Women%20Have%20a%20RenaissanceX.doc

- Op Cit Zajko

- Lillian Doherty, ‘Putting the Women Back Into the Hesiodic Catalogue of Men’ in V.Zajko and M.Leonard eds ‘Laughing With Medusa’,(London: Oxford University Press,2006)

- Virginia Woolf,A Room of One’s Own,

- William Butler Yeats, Leda and the Swan

- Adrienne Rich, ‘When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-vision’, http://www.jstor.org/stable/375215?origin=JSTOR-pdf

- Op Cit Zajko

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Doherty Lillian. ‘Putting the Women Back Into the Hesiodic Catalogue of Men’ in Zajko Vanda and Leonard M eds ‘Laughing With Medusa’. London: Oxford University Press,2006.

Doty, William.G. Mythography:The Study of Myths and Rituals. London: The University of Alabama Press,2000

Dowden Ken and Livingstone Niall. “Thinking Through Myth, Thinking Myth Through”. A Companion to Greek Mythology .Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell Ltd,2001.

Kirk,G.S. ‘ Myth: Its Meaning and Functions in Ancient and Other Cultures’ in

Doty, William.G. Mythography:The Study of Myths and Rituals. London: The University of Alabama Press,2000

Neils Jennifer. “Myth and Greek Art:Creating a Visual Language”. Woodard Robert ed. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology. New York:Cambridge University Press,2007.

Rich Adrienne. When We Dead Awaken: Writing As Re-Vision. http://www.jstor.org/stable/375215?origin=JSTOR-pdf

Woodard Robert ed. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology. . New York:Cambridge University Press,2007.

Woolf Virginia . A Room Of One’s Own.

Zajko Vanda. “Women and Greek Myth”. Woodard Robert ed. The Cambridge Companion to Greek Mythology. New York:Cambridge University Press,2007.

Images

Mosaic, Tintoretto, Moreau, Boucher, Cezanne – https://venetianred.wordpress.com/tag/leda-and-the-swan/

Michelangelo, da Vinci, Correggio, Timotheos,Dali- Google images